AN APPEAL FOR SUPPORT

- We are in need of support to meet expenses relating to some new and essential software, formatting of articles and books, maintaining and running the journal through hosting, correrspondences, etc. If you wish to support this voluntary effort, please send your contributions to

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road Suite C

Bloomington

MN 55438, USA.

Also please use the AMAZON link to buy your books. Even the smallest contribution will go a long way in supporting this journal. Thank you. Thirumalai, Editor.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- COMMUNICATION VIA EYE AND FACE in Indian Contexts by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION

VIA GESTURE: A STUDY OF INDIAN CONTEXTS by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - CIEFL Occasional

Papers in Linguistics,

Vol. 1 - Language, Thought

and Disorder - Some Classic Positions by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - English in India:

Loyalty and Attitudes

by Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education

by B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI

AND MALAYALAM

by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D. - LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS

IN TAMIL

by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D. - An Introduction to TESOL:

Methods of Teaching English

to Speakers of Other Languages

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Transformation of

Natural Language

into Indexing Language:

Kannada - A Case Study

by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. - How to Learn

Another Language?

by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Verbal Communication

with CP Children

by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D.

and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Bringing Order

to Linguistic Diversity

- Language Planning in

the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- Lord Macaulay and

His Minute on

Indian Education - In Defense of

Indian Vernaculars

Against

Lord Macaulay's Minute

By A Contemporary of

Lord Macaulay - Languages of India,

Census of India 1991 - The Constitution of India:

Provisions Relating to

Languages - The Official

Languages Act, 1963

(As Amended 1967) - Mother Tongues of India,

According to

1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- JULY 2004 - INDEX OF AUTHORS

AND THEIR ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- JULY 2004

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports to thirumalai@bethfel.org, or send your floppy disk (preferably in Microsoft Word) by regular mail to:

M. S. Thirumalai

6820 Auto Club Road, Suite C.,

Bloomington, MN 55438 USA. - Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2004

M. S. Thirumalai

AN EXPLORATION INTO

LINGUISTIC MAJORITY-MINORITY RELATIONS IN INDIA

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D.

ABSTRACT

The Majority-Minority relation between populations is an interesting and important factor in the development and nation-building discourse. It assumes different contours at different times in any country. At present, India is witnessing a transition. The Indian political plane is so volatile that it may overcrowd, eliminate, submerge, or transform the kind of identity assertions that we have been witnessing for the past half a century or so. This paper intends to capture this transitional process through exploring the linguistic majority-minority relations using statistical, economic, social, political and other dimensions including Constitutional, legal, geographical (nation : region), social / religious, ethnic(tribal : non-tribal), etc. Interdependency of these factors is highlighted. My aim in this paper is to find out the rational behind certain binary classifications such as national : regional, social : religious, etc., and unravel the intention of the nation-builders, and the kinds of safeguards provided to the minorities, even as I identify the use or misuse of such provisions by the 'minorities', and ultimately to assess whether this classification or categorization is healthy, and whether this classification has helped the languages and people groups in any significant way.

This paper discovers, analyzes, and describes the relation between the linguistic majority-minority populations, and demonstrates, among other things, that the linguistic relation continually evolves and, in reality, is relative to the socio-political and economic conditions. In addition, the recent processes of globalization, more clearly exemplified in the rise of gigantic multi-national Indian corporations, urbanization, focus on English education, zest for jobs abroad, and the growth of a vast middle class spanning across ethnic and linguistic boundaries are also discussed. These additional processes blunt the focus on the majority-minority relations. This paper also raises the question, as already suggested, whether we can take the categorization of majority-minority as a stable situation, or whether there are other linguistic or religious processes, which could suddenly occupy the center-stage, and change the direction of our discourse.

1. INTRODUCTION

Indian multilingualism is characterized by a very interesting scene: more languages are now involved as participants in the current increase in bilingualism and tri-lingualism; more than one script is used to write many languages, and many scripts used to write a single language; many Indian languages share a similar set of linguistic features across the language families, etc.In this multilingual context, the relation between the majority and minority languages has not been stable. We notice that historically some minority languages have wielded greater social and political power than the majority languages, and have demanded and received strong loyalty for them from the majority. Once Sanskrit, and now for over two hundred years, English, are minority languages. But they had, and continue to have, power to attract the majority language speakers(or speakers of Major Indian Languages) due to their social prestige and the economic power. They are the second languages of the elite.

The number of mother tongue speakers of English is on the decline, according to the decennial Census - 1961:223788;1971: 191595;1981: 202440; 1991:178598. At the same time, the number of speakers declaring English as second or third language is increasing. As per the 1991 Census, the percentage of bilinguals and tri-linguals in English(8.00%, 3.5% respectively) is more than those of the same categories in Hindi(6.15%, 2.16%).

In recent past, the majority-minority language relations have depended upon various factors and diverse issues like the Constitutional provisions, population, language use statistics, legal interpretations, and, above all, political compulsions and interpretations. The majority-minority relations are influenced also by factors such as whether the speakers of a language or a group of languages or dialects have a religious or tribal back up support, and whether the context of such identities jibe well with the historical context in which the issue is raised and discussed. An Indian language having a state, ie., a defined geographic territory for its spread in terms of bilingualism, tri-lingulism and opportunities for its use in more and more functional domains, contributes for development and change of majority and minority relation. We may recall here that Sindhi and Urdu were accorded the status of a Scheduled language in the Constitution of India even when they did not or do not have a defined territory.

The quality and importance of the majority-minority relation at the time of partition of India and in the years after independence of the nation do not exist now; nor is the context during the 1960s and 1970s going to be repeated now. At the same time, the present lack of focus or urgency on maintaining a proper majority-minority linguistic relation may not continue for ever.

2. THE NOTION OF MINORITY

The notion of majority does not need any introduction or explanation, since it is more or less a self-evident fact, whatever be the measures we adopt in defining it. On the other hand, the notion of minority needs to be defined in every new context due to its multidimensionality. The Oxford Dictionary defines minority as "the condition or fact of being smaller, inferior, or subordinate; smaller number or part; a number which is less than half the whole number. Similarly, relation is "an existing connection, ... a significant association between or among things."

First of all, it is the number count, or the statistical divide between two or more entities under consideration, resulting in majority/minority division. The minor, since it is numerically less, is perceived to be week and has to be empowered separately through special measures to make it equal to the majority. In this power relation, the minor is supposed to be subordinate to the major.

3. LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA

The concept of linguistic minority in India is a relational one, and no one definition captures the essence of all kinds of linguistic minorities that the national planning and language planning has thrown up in the country. In the British India, India was perceived to have 'English' 'the Indian vernaculars', 'provincial languages', and other 'dialects'. Then, the word 'minorities' meant mainly the religious minorities. This was inevitable because, for the British, the major power to contend with in the acquisition of Indian territories was the Mughal empire, which happened to be a Muslim rule over the majority Hindu. Their world view was thus shaped by this dichotomy. The progress of the struggle for the independence of India since the partition of Bengal and even before this point in modern history, revolved around the world view that the India consisted of Hindu-Muslim societies.

The Notion of linguistic minorities is largely the contribution of independent India. The British went after their administrative convenience. Moreover, several of the Indian territories they acquired and integrated were already multilingual under some princely rule or the other. They have established themselves in their chosen settlements long before their incessant acquisition of territories began. Their central trading posts had become multilingual, and the empire began spreading out from these factory towns. The English became the language of government; there was no compulsion on them to divide the territories on the basis of the dominant Indian languages used in each of these territories. Growing linguistic identity consciousness among the people of various presidencies and provinces became a focal point for the Indian National Congress in their attempt to mobilize popular support for the struggle for independence. The Congress in many of its resolutions recognized the popular aspirations and thus they could not avoid creating linguistically organized states. Thus, focused linguistic majority-minority concept is mainly the result of the creation of linguistic states and choice/categorization of language(s) by the language policy of the Union and the governments of States and Union Territories.

The Report of the State Reorganization Commission (1955 : 260) recommended that

Constitutional recognition should be given to the right of linguistic minorities to have instruction in their mother-tongues at the primary school stage subject to a sufficient number of students being available." Hence, after the reorganization of the states in 1956, Articles 350 A and 350 B were included into the Constitution which state that: It shall be the endeavor of every State and of every local authority within the State to provide adequate facilities for instruction in the mother-tongue at the primary stage of education to children belonging to linguistic minority groups; 350(1) There shall be a special officer for linguistic minorities to be appointed by the President.(2) It shall be the duty of the special officer to investigate all matters relating to the safeguards provided for linguistic minorities under this Constitution and report to the President upon these matters at such intervals as the President may direct, and the President shall cause all such reports to be laid before each House of Parliament, and sent to the government of the states concerned.

The Indian linguistic minorities are the products of State policy. The reorganization provided space for the growth of many regional languages. Now, the states are further reorganized on the lines of issues, like underdevelopment and development of the regions within a state. The demands are on for their further division of linguistic states for social and economic reasons. These divisions are on the lines of some of the divisions that existed in pre-independence India, such as provinces. These further divisions may not create some more linguistic minorities.

Another important feature in India's linguistic scenario is the of layering of linguistic minorities unlike in most of the other countries, and also existence of different kinds of linguistic minorities. Many times, the identification of these kinds is domain-specific, or geography- specific. Speakers of one language are minority at one level, and they are majority at another level. Speakers of some of the languages remain minority at all the levels. Some of them tend to have a religious or tribal affiliation added to their feature as linguistic minority. And hence, the Constitution of India does not define as to who the linguistic minorities are. However, as we saw above, the Constitution has provided safeguards for them. Hence, the definition of linguistic minorities is generally taken for granted as a known commonsense fact than a concept to be defined or identified. The definition used to identify them is largely context-bound.

3. STATE AS A UNIT

The Supreme Court of India in the matter of TMA Pai Foundation and others vs State of Karnataka [Writ petition(Civil)No.317 of 1995]on October 31, 2002 decided that 'minority' within the meaning of Article 30 which provides right to the minorities to establish and administer educational institutions is "…for the purpose of determining the minority, the unit will be the State and not the whole of India. Thus, religious and linguistic minorities, who have been put at par in Article 30, have to be considered State-wise". And at the same time, it said that "Article 30 is a special right conferred on the religious and linguistic minorities because of their numerical handicap and to instill in them a sense of security and confidence, even though the minorities can not be per se regarded as weaker sections of underprivileged segments of the society."(emphasis added) This is not the end of the criteria to identify the linguistic minorities. There are other criteria too.

4. TALUK AS A UNIT

For the purpose of the implementation of Official Language(s) Act(s) of different states, the taluk is taken as a geographic territory to decide about whether a language is a minority language or not. If within a taluk a language spoken by more then 15% of the total population of the said taluk, that language is considered as a minority language in that context. The official documents, announcements of the government in the official language of the state have to be translated into those languages too, for use by the speakers of that language.

5. SCHOOL AS A UNIT

As agreed to in the Chief Ministers Conference in 1961, whenever there are 40 students in a school, or 10 in a class-room, desiring to learn in their mother tongue at the primary level, teaching will have to be done by appointing one teacher. Here normally the mother tongue of the child is different from the regional language and generally a minority language in the numerical sense.

6. THREE DIFFERENT KINDS OF LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA

Also, the tag of 'linguistic minority' is not applied normally, mechanically, or automatically. A language needs to be officially recognized or declared as a minority language by the competent authority. It may be noted that the Official Language Acts of the States recognize a language as the Official Language and identify other minority languages which are permitted for use in the administration in a specific region or regions of a state.

Under these circumstances, three different kinds of linguistic minorities could be identified in India and they are:

- Linguistic minorities

- Linguistic minorities with tribal affiliation

- Linguistic minorities with religious affiliation

Indian multilingualism has thrown up a mosaic of linguistic minorities. Apart from this, as we already saw, practically the existence of linguistic minorities officially stretches across different levels. Levels and different kinds of linguistic majorities-minorities in India are:

1. Hindi (including all mother tongues cobbled up within it for creating a statistical majority) vs all other Indian languages [1 vs 113]

If we see the way the statistical majority of Hindi is growing, it is amazing. Different mother tongues are combined to make a linguistic majority.(A forthcoming paper of mine that discusses the processes of Census relating to language classification in the last 100 years or more reveals that this cobbling up is not an accident and that this process is applied to other major non-Hindi mother tongues as well.)

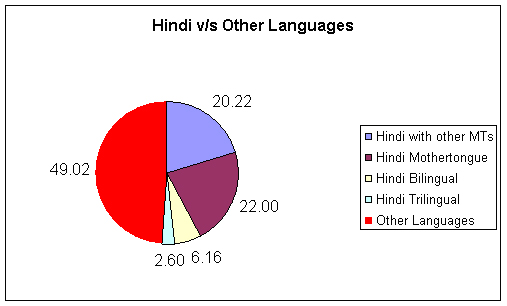

If this kind of clustering is not done, the linguistic demography of Hindi will be different. It is mother tongue of 22% of population; it has 20.22% of mother tongues clustered under it as a language; it is used as second language by 6.16%; and as third language by 2.60% - totaling to 50.98%. Hindi crosses the magic figure of definition of majority by being above 50% in 1991 Census.

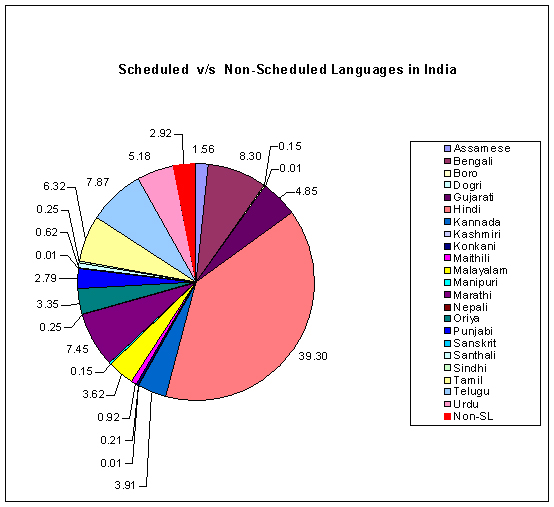

2. Scheduled Languages (all these being considered major languages) vs Non-Scheduled Languages (all these being considered minor languages).[22 vs 91]

This is an open ended list with 22 languages in the list today. At the first instance when the Schedule was formed it had 14 languages. It has been expanded 3 times-to include Sindhi in 1969, Konkani, Manipuri and Nepali in 1993 and in 2003 to include Bodo, Dogri, Maithili and Santhali.

The Scheduled languages constitute 97.00% of the population of India. The rest of the people speak non-scheduled languages.

3. Regional languages (recognized as official languages of the concerned States) vs all other languages used in that state including Indigenous languages and other languages (of past or present migrants from other places). The declared 16 official languages in the country are: Assamese, Bengali, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Konkani, Malayalam, Nepali, Manipuri, Marathi, Oriya, Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu and Urdu. [16 vs 97]

4. Notified tribal languages vs non-notified tribal languages: The following have been scheduled as tribal languages by a Presidential Order published in the Gazette of India, Part II, Section 1, dated August 13, 1960: Abor/Adi, Anal, Angami, Ao, Assuri, Agarva, Bhili, Bhumij, Birhor, Binija/ Birijia, Bodo including Kachari, Mech, Chang-Naga, Chiri, Dafla, Dimasa, Gadaba,Garo, Gondi, Ho, Halam, Juang, Kabui, Kanawari, Kharia, Khasi, Khiemnungam, Khond/Kandh, Koch, Koda/Kora, Kolami, Konda, Konyak, Korku, Kota, Korwa, Koya, Kurukh/Oraon, Lushai/Mizo, Mikir, Miri, Mishmi, Mru, Mundari, Nicobarese, Paite, Parji, Rabha, Rangkhul, Rengma, Santali, Savara, Sema,Tangkhul,Thado,Toda,Tripuri [The list given here is not complete). [60 vs all other tribal languages]

5. Languages declared as minority languages for specific purposes vs other non-declared languages. In Karnataka Malayalam, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Kodagu, Tulu, Konkani are declared as minority languages for administrative purposes in specific taluks in the year 2004 as per 1991 Census. But Banjari, Yerava, Soliga etc., are officially neither major languages nor minor languages.

6. Regional languages having majority status in one or more states but having minority status in another state. All the Official languages of the States are major languages in the respective sates and minority languages in other states.

7. Languages with the literary tradition and the languages without such a tradition. The languages recognized by the Central Sahitya Akademi and the languages recognized by some of the states for literary purposes vs the languages who have literature but lack such recognition.

8. Recognized linguistic minorities vs unrecognized linguistic minorities. The languages of this later group do not find any place and get included under 'other languages'.

7. LINGUISTIC RRELATIONS

The issues relating to majority and minority situations are discussed by Schermerhorn(1970), Paulston(1978) and Singh(1987). It is demonstrated that a group tries to get a dominant position and push others to back stage; there will be integration, which will be proportionate to percentage of bilinguals, network of institutions, control of resources, character of subordinate group or groups - assimilationist, pluralist, secessionist, or militant; sunflower syndrome - all looking towards the sun and for various reasons, none liking the other.

However, the above 8 groups of majority minority language situations exhibit different kinds of majority/minority relationships and not uniform relationship which can be analyzed and interpreted along with looking into the extent the minority rights are used or misused.

8. DYNAMISM

In the context of Indian multilingualism, the majority-minority status is not static and permanent, but it is dynamic and ever evolving. The position or status of many of the languages is changing. We have seen such movement of languages within the stock of Indian languages in the past 50 years. Recent movement of Maithili from the status of a mother tongue under the umbrella language Hindi to an independent status of a Scheduled language and movement of Boro, Dogri, and Santhali from the status of Non-Scheduled languages to Scheduled languages are such examples. The change of position is always supposed to be towards growth and prosperity of languages and their speakers. (To what extent such claims are really achieved is another matter that needs an intensive investigation from different angles.) Normally no language has explicitly objected to such progressive movement of other languages, so long as their already designated space is not to be shared.

A language having or acquiring majority status (and such type of movement) is the result of a combination of many linguistic and nonlinguistic factors. It affects the language that has moved and does not affect the position that it has left.

For the same language, both acquiring the status of a Scheduled language in the country and demanding the status of a minority language in a state, are considered important by the linguistic agenda of speakers of different languages.

That the Tulu speakers demand for the status of scheduled language and at the same time they seek the minority language status for themselves in Karnataka is one such example. Contradictions are truly galore in the linguistic scenario.

One curious element in the recognition of Indian languages is observed. First, the speakers seek entry for their language into Schedule VIII; then, if the speakers of the language are in a geographically contiguous place, they seek a separate state; and then, seek the status of official language in the concerned state.

The case of Konkani and Goa is an example for this phenomenon. May be one day or the other, recognition of Maithili may lead to creation of the state of Mithila. Recognition of Bodo(Dec 2003) preceded the creation of Bodoland Autonomous Council (Feb 1993).The formation of different autonomous councils (Autonomous Councils for Mising, Rabha, Lalung etc.,) which have a language as a base too may follow the same pattern.

9. SPEED

One of the important and well-argued phenomenon of super-ordinate and subordinate relations among the languages is the of spread of super-ordinate languages among the speakers of subordinate languages. Through this, major languages become languages of wider communication. This results, unfortunately, in the non-spread of minority languages among majority languages. So, minor language speakers are necessarily more bilingual (38.14%) and trilingual (28%) than the majority language speakers-bilinguals(18.72%) or tri-linguals (7.22%).

10. LEGALITY

There are safeguards to see that minority languages are not vanishing but grow and survive and their living is not obstructed by the majority languages. But in spite of these three situations have developed in the country due to legal pronouncements and practice of legal provisions by the linguistic minorities.

- Supremacy of English in education: The Tamil Nadu High Court in its order (The Madras Law Journal Reports-2000:578) of said that the career opportunities will be more advantageous to those who have studied in the English medium than using the Tamil medium. Compelling the students to study in Tamil will affect their career, and doom their future prospects.

- Regional languages as languages of integration: In the course of 50 years or so, Hindi, English at one level and at another level the regional languages have grown as lingua franca of the concerned state and become languages of wider communication. The Supreme Court (2004)while debating teaching of Marathi in the minority schools in Maharastra said that teaching of regional language compulsorily in the State is not violative of the rights of the linguistic minorities and "…while living in a different State, it is only appropriate for the linguistic minority to learn the regional language. The resistance to learn the regional language will lead to alienation from the mainstream of life resulting in linguistic fragmentation within the State, which is an anathema to national integration.

- Misuse of provisions for linguistic minorities: The genuine intention of providing safeguards to linguistic minorities in the form of liberty to establish Institutions by linguistic minorities under the Constitutional provisions has been used for commercialization of education, mainly higher and professional education and hardly any thing has been done or contributed for the purpose for which such Institutions have been established in letter and spirit of the Constitutional provisions. Minority languages are remaining as identity symbols and tools for bargaining resources for economic development rather than development of languages.

1. This is a Draft working paper presented in the 32nd Conference of the Dravidian Linguistic Association held at Warangal, Andhra Pradesh, India from June 10 to 12, 2004.

2. An important suggestion was offered during the discussion on this paper: examine whether it is possible to make a distinction between the 'minor language' and 'minority language.' The author is currently engaged in examining this issue and he proposes to further elaborate on these points when he expands this paper. The author is grateful to the participants of the conference for their valuable suggestions.

CLICK HERE FOR PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION.

A BRIEF SURVEY OF HEBBAR TAMIL'S VERB MORPHOLOGY | SOCIAL ASPECTS OF MOODS IN MALAYALAM | INDIANIZATION OF ENGLISH MEDIA IN INDIA : AN OVERVIEW | I WANT TO LEARN TIBETAN | LEARNING KANNADA BY STUDENTS WHOSE MOTHER TONGUE IS KANNADA - SOME PROBLEMS | LANGUAGE NEWS THIS MONTH - The Case of a Missing Preposition, etc. | AN EXPLORATION INTO LINGUISTIC MAJORITY-MINORITY RELATIONS IN INDIA | A LINGUISTIC STUDY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM AT THE SECONDARY LEVEL IN BANGLADESH - A COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH TO CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT | HOME PAGE | CONTACT EDITOR

B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D.

Central Institute of Indian Languages

Mysore 570006, India

mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net

Send your articles

as an attachment

to your e-mail to

thirumalai@bethfel.org.