AN APPEAL FOR SUPPORT

- We seek your support to meet expenses relating to some new and essential software, formatting of articles and books, maintaining and running the journal through hosting, correrspondences, etc. You can use the PAYPAL link given above. Please click on the PAYPAL logo, and it will take you to the PAYPAL website. Please use the e-mail address thirumalai@mn.rr.com to make your contributions using PAYPAL.

Also please use the AMAZON link to buy your books. Even the smallest contribution will go a long way in supporting this journal. Thank you. Thirumalai, Editor.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- SANSKRIT TO ENGLISH TRANSLATOR ...

S. Aparna, M.Sc. - A LINGUISTIC STUDY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM AT THE SECONDARY LEVEL IN BANGLADESH - A COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH TO CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT by

Kamrul Hasan, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION VIA EYE AND FACE in Indian Contexts by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION

VIA GESTURE: A STUDY OF INDIAN CONTEXTS by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - CIEFL Occasional

Papers in Linguistics,

Vol. 1 - Language, Thought

and Disorder - Some Classic Positions by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - English in India:

Loyalty and Attitudes

by Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education

by B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI

AND MALAYALAM

by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D. - LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS

IN TAMIL

by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D. - An Introduction to TESOL:

Methods of Teaching English

to Speakers of Other Languages

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Transformation of

Natural Language

into Indexing Language:

Kannada - A Case Study

by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. - How to Learn

Another Language?

by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Verbal Communication

with CP Children

by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D.

and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Bringing Order

to Linguistic Diversity

- Language Planning in

the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF LINGUISTIC RIGHTS

- Lord Macaulay and

His Minute on

Indian Education - In Defense of

Indian Vernaculars

Against

Lord Macaulay's Minute

By A Contemporary of

Lord Macaulay - Languages of India,

Census of India 1991 - The Constitution of India:

Provisions Relating to

Languages - The Official

Languages Act, 1963

(As Amended 1967) - Mother Tongues of India,

According to

1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- FEBRUARY 2005 - INDEX OF AUTHORS

AND THEIR ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- FEBRUARY 2005

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports (preferably in Microsoft Word) to thirumalai@bethfel.org.

- Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2004

M. S. Thirumalai

INDIAN RHETORIC IN THE PARLIAMENT OF RELIGIONS, 1893

Speeches of Vivekananda and OthersM. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

INDIAN AWARENESS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Ram Mohun Roy (1772-1833), a man of unorthodox ideas, full of zeal for western ideas and eastern resurgence, was actively involved in the re-interpretation of Hindu thought and precepts in western parlance. In 1835, the Minute of Macaulay became the cornerstone of future Indian education with English as the primary tool. In 1885, the Indian National Congress was founded, a great symbolic event that led to the resurgence of Indian political thought and aspirations. In 1893, the time was ripe for an Indian to present to the western audience and to the world the Vedantic ideas of Hinduism, and claim leadership among the nations for spirituality. In the process, India as a single and united nation got a wider notice, helping the growth of national consciousness in India.

VIVEKANANDA'S ARRIVAL IN AMERICA

Vivekananda was a product of his time; he arrived in America at a time when the Unitarian ideas have already seized the imagination of leading writers and thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882). He arrived in America for the Parliament of Religions, an alternate name for the World's Congress of Religions, and stayed there for six years (?), establishing several centers of discussion groups.

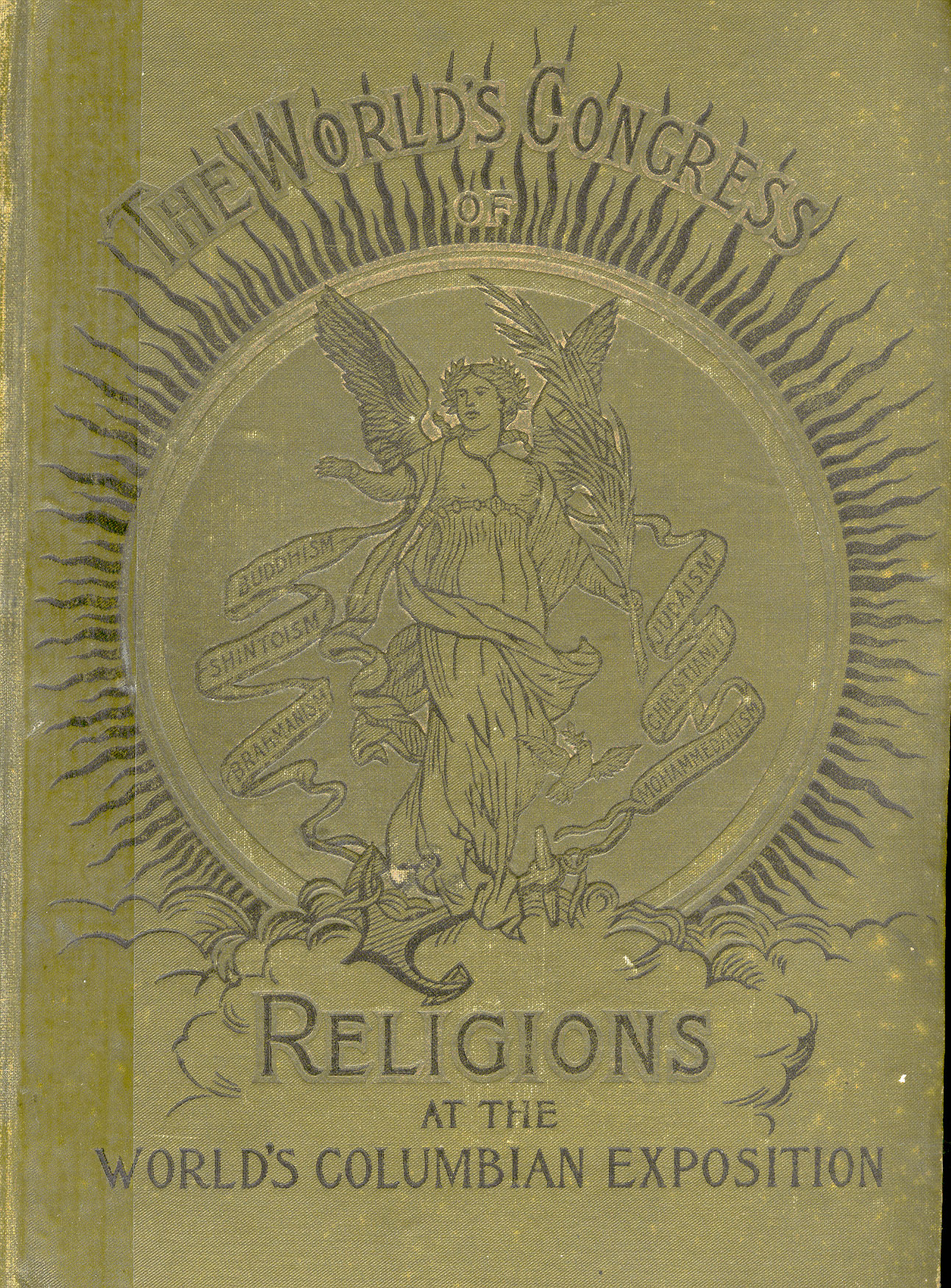

THE WORLD'S CONGRESS OF RELIGIONS OR PARLIAMENT OF RELIGIONS

The World's Congress of Religions was held in Chicago from Monday, September 11, 1893 for 18 days, at the Art Institute under the auspices of the World's Columbian Exposition. The proceedings of the Congress, giving "the addresses and papers delivered before the Parliament" were published in a volume edited by J. W. Hanson through the International Publishing Company in Chicago in 1894. This volume has an interesting introductory chapter with the title "Opening of the Parliament." This statement claims that the volume contains "the cream of the great religious parliament and congresses."

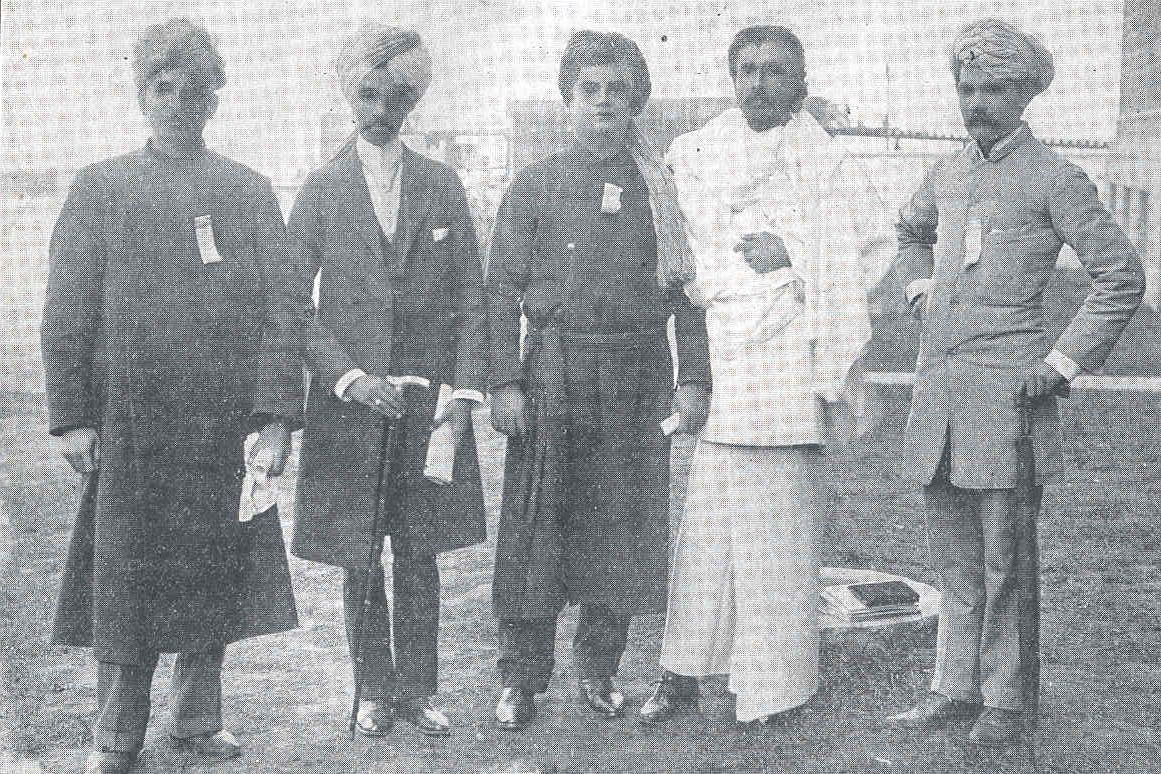

On the opening day, there were 43 delegates seated on the dais of the hall. Two of these were Japanese translators for the Japanese speakers. Of these 41 delegates, it appears from the list that there were 10 with Indian names seated on the dais. Indeed, 25% of the participants came from far off India! If we include the westerners who presented papers on Indian religions and thought, then, a significant part of the membership of the delegates who were seated on the dais came from India.

INDIAN DELEGATES ON THE DAIS

The names of persons from India who were seated on the dais were as follows:

- Rajah Ram, of the Punjab.

- Birchand Raghavji Gandhi, Honorary Secretary of the Jain Asociation, of India, Bombay.

- Rev. P.C. Mazoomdar, India.

- H. Dharmapala, India. (Actually he was from Ceylon, which was part of British India at that time.)

- Miss Jeanne Serabji, Bombay.

- Swami Vivekanda, Bombay.

- Professor Chakravarti, Bombay.

- B. B.Nagarkar, Bombay, "representative of the religion of the Bromo, Samaj."

- Jinda Ram, India.

- The Rev. Morris Phillips, of Madras.

THE ELOQUENT MR. P. C. MAZOOMDAR

The first Indian delegate to speak in the inaugural function in response to the welcome speeches was "the eloquent P. C. Mazoomdar, of the Brahmo-Somaj." Mazoomdar recognized the fact that there was a good representation from India, and so he began as follows:

Leaders of the Parliament of Religions, Men, and Women of America: The recognition, sympathy, and welcome you have given to India today are gratifying to thousands of liberal Hindu religious thinkers, whose representatives I see around me, and on behalf of my countrymen, I cordially thank you. India claims her place in the brotherhood of mankind, not only because of her great antiquity, but equally for what has taken place there in recent times. Modern India has sprung from ancient India by a law of evolution, a process of continuity which explains some of the most difficult problems of our national life. In prehistoric times our forefathers worshipped the great living Spirit, God, and after many strange vicissitudes we, Indian theists, led by the light of ages, worship the same living Spirit, God, and none other. No individual, no denomination, can more fully sympathize or more heartily join your conference than we men of the Brahmo-Somaj, whose religion is the harmony of all religions, and whose congregation is the brotherhood of all nations.

Note that even as Mazoomdar emphasized his Brahmo-Somaj theology, he was very conscious of his Indian background. We notice a yearning for the recognition of India, and for India joining the brotherhood of nations, in his address. He actually set the tone for all other Indian delegates who vie with one another to establish and demonstrate their Indian identity. We see this urge to be part of the comity of nations stated time and again in the speeches of Gandhi and Nehru. Nehru's Tryst with Destiny speech clearly shows this urge. To be part of the world and winning it for India appears to be a theme that continues to propel Indian leaders and thinkers all the time. As we shall see, there were different styles adopted by different Indian delegates, but every one was keen to be seen as an India. Mazoomdar referred to his countrymen on the dais as representing the liberal Hindu thinkers of India. His idea of liberalism is, it appears to me, is the avoidance of elements that hamper progress such as the so-called superstitious practices of the day.

DHARMAPALA

Dharmapala from Ceylon saw in the Parliament of Religions a semblance to the congress called by the Emperor Asoka. He was full of enthusiasm for the possibility of carrying out Buddhist missionary goals. Dharmapala brought

the good wishes of four hundred and seventy-five millions of Buddhists, the blessings and peace of the religious founder of that system which has prevailed so many centuries in Asia, which has made Asia mild, and which is today, in its twenty-fourth century of existence, the prevailing religion of the country. I have sacrificed the greatest of all work to attend this parliament. I have left the work of consolidation - an important work which we have begun after seven hundred years-the work of consolidating the different Buddhist countries, which is the most important work in the history of modern Buddhism. When I read the programme of this parliament of religions I saw it was simply the re-echo of a great consummation which the Indian Buddhists accomplished twenty-four centuries ago.

At that time Asoka, the great emperor, held a council in the city of Patma of one thousand scholars, which was in session for seven months. The proceedings were epitomized and carved on rock and scattered all over the Indian peninsula and the then known globe. After the consummation of that programme the great emperor sent the gentle teachers, the mild disciples of Buddha, in the garb that you see on this platform, to instruct the world. In that plain garb they went across the deep rivers, the Himalayas, to the plains of Mongolia and the Chinese plains, and to the far-off beautiful isles, the empire of the rising sun; and the influence of that congress held twenty-one centuries ago is today a living power, because you everywhere see mildness in Asia.

Go to any Buddhist country and where do you find such healthy compassion and tolerance as you find there? Go to Japan, and what do you see? The noblest lessons of tolerance. Go to any of the Buddhist countries and you will see the carrying out of the programme adopted at the congress called by the Emperor Asoka.

Why do I come here today? Because I find in this new city, in this land of freedom, the very place where that programme can also be carried out. For one year I meditated whether this parliament would be a success. Then I wrote to Dr. Barrows that this would be the proudest occasion of modern history, and the crowning work of nineteen centuries. Yes, friends, if you are serious, if you are unselfish, if you are altruistic, this programme can be carried out, and the twenty-fifth century will see the teachings of the meek and lowly Jesus accomplished.Speaking from the perspective of Buddhism, Dharmapala had the compulsion of focusing on the international characteristics of Buddhism, not necessarily on Ceylon or India. His agenda was to show case Buddhism, not any one particular country. His goal was to bring Buddhism to America, to bring the civilizational effects of Buddhism just as it happened throughout Asia because of the initiative of Emperor Asoka. India came to be mentioned, but it is Asia, a continent of Buddhist nations, that gets the major share.

There is a separate article published in the volume by Dharmapala, whereIN he presents an able interpretation and relevance of Buddhism for the world. Nationalism is under check there also. On the other hand, the delegates from India would display their Indian identity more prominently in all their speeches in the Parliament.

THE JAIN REPRESENTATIVE, VIRCHAND A. GANDHI

Virchand A. Gandhi made a brief speech in the inaugural function. The volume reports as follows:

Virchand A. Gandhi, of Bombay, represented Jainism, a faith, he said, older than Buddhism, similar to it in its ethics, but different from it in its psychology, and professed by one million five hundred thousand of India's most peaceful and law-abiding citizens. You have heard so many speeches from eloquent members, and as I shall speak later on at some length, I will, therefore, at present, only offer, on behalf of my community and their high priest, Mony Atma Ranji, who I especially represent here, our sincere thanks for the kind welcome you have given us. This spectacle of the learned leaders of thought and religion meeting together on a common plat form, and throwing light on religious problems, has been the dream of Atma Ranji's life. He has commissioned me to say to you that he offers his most cordial congratulations on his own behalf, and on behalf of the Jain community, for your having achieved the consummation of that grand idea of convening of a parliament religions.

Virchand Gandhi's speech is typical of Indian speech on such occasions. He considered himself a humble servant of his high priest, carrying out the command of the high priest. This form of rhetoric is often the mode that the disciples, students, and servants of superiors adopt in the public domain. We consider it our duty to mention our superiors even though they are not present. Truly Indian in many respects, words from English, but delivered in characteristic Indian style. Tradition demands it, and we simply follow it.

PROFESSOR C. N. CHAKRAVARTI ON THEOSOPHY

The opening chapter reports that,

Prof. C. N. Chakravarti represented Indian theosophy. He said: I came here to represent a religion, the dawn of which appeared in a misty antiquity of which the powerful microscope of modern research has not yet been able to discover; the depth of whose beginnings the plummet of history has not been able to sound. From time immemorial spirit has been represented by white, and matter has been represented by black, and the two sister streams which join at the town from which I came, Allahabad, represent two sources of spirit and matter, according to the philosophy of my people. And when I think that here, in this city of Chicago, this vortex of physicality, this center of material civilization, you hold a parliament of religions; when I think that, in the heart of the world's fair, where abound all the excellencies of the physical world, you have provided also a hall for the feast of reason and the flow of soul, I am once more reminded of my native land.

'Why?' Because here, even here, I find the same two sister streams of spirit and matter, of the intellect and physicality, joining hand in hand, representing the symbolical evolution of the universe. I need hardly tell you that, in holding this parliament of religions, where all the religions of the world are to be represented, you have acted worthily of the race that is in the vanguard of civilization, a civilization the chief characteristic of which, to my mind, is the widening toleration, breadth of heart, and liberality toward all the different religions of the world. In allowing men of different shades of religious opinion, and holding different views as to philosophical and metaphysical problems, to speak from the same platform aye, even allowing me, who, I confess, am a heathen as you call me to speak from the same platform with them, you have acted in a manner of worthy of the motherland of the society which I have come to represent today. The fundamental principle of that society is universal tolerance; its cardinal belief that, underneath the superficial strata, runs the living water of truth."

Professor Chakravarti drew a picture of India that would continue to be referred to in all speeches, and in the India political platforms. This is a picture of India that the elitist and non-elitist classes believed in as truly prevalent. The respect that he received was because his mother land deserved this respect. Regional attitudes were not exhibited. India remained in his and others' speeches as a single colossal nation with a past that every one could be proud of.

THUNDER FROM BENGAL - SWAMI VIVEKANANDA'S RESPONSE TO WELCOME

Next was the address of Vivekananda, in the opening ceremony. Swami Vivekananda was listed as a delegate from Bombay, India, a monk. The opening chapter says,he responded: It fills my heart with joy unspeakable to rise in response to the warm and cordial welcome which you have given us. I thank you in the name of the most ancient order of monks in the world; I thank you in the name of the mother of religion, and I thank you in the name of the millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects.

Note the three elements or basic assumptions of Vivekananda: most ancient order of monks in the world, mother of religion, and millions and millions of Hindu people of all classes and sects. He presents himself as representing these three important elements. The matter did not end there. In the following paragraph he would go one step further to characterize Hinduism as not only a religion of tolerance but also of universal acceptance. With this statement, he would claim a much wider scope for Hinduism and India:

My thanks, also, to some of the speakers on this platform who have told you that these men from far-off nations may well claim the honor of bearing to the different lands the idea of toleration. I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions to be true.

Vivekananda distinguished Hinduism not only from the major religion of Christianity of his audience by this sentence, but also from Buddhism. And then he would ascribe this characteristic to India. While toleration is a characteristic of Buddhism, Vivekananda would like to emphasize the ready and willing acceptance of all religions as true in comparison to Buddhism.

Here below is an interesting linguistic argument of Vivekananda:

I am proud to tell you that I belong to a religion into whose sacred language, Sanskrit, the word seclusion is untranslatable.

He relates this inability to seclude people or theology to the magnificent Indian tradition of welcoming all with open arms into India.

Then he strikes a sympathetic cord in the hearts of his listeners by referring to the hoary past of the generosity of Indian people to all the nations that visited them and lived among them. His religion and nation become one in this statement.

I am proud to belong to a nation which has sheltered the persecuted and the refugees of all religions and all nations of the earth. I am proud to tell you that we have gathered in our bosom the purest remnant of Israelites, a remnant which came to southern India and took refuge with us in the very year their holy temple was shattered to pieces by Roman tyranny. I am proud to belong to the religion which has sheltered and is still fostering the remnant of the grand Zoroastrian nation. I will to you, brethren, a few lines from a hymn which remember to have repeated from my earliest boyhood, which is every day repeated by millions of human beings: 'As the different streams, having their sources in different places, all mingle their water in the sea, oh, Lord, soothe different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee.'

Note that the illustrations are not taken merely from only one region. These were taken deliberately from the different regions of India: the south and the west, and the people groups chosen, especially the case of the Israelites, are quite well known. India, from times immemorial, gave asylum to people of various religions in their dire need. What else best illustrates the magnanimity of the nation? Fortunately, we saw this enduring quality demonstrated several times in the twentieth-century. I am not sure of the future. In any case, Vivekananda was ready with linguistic and sociological examples, and he could present these examples with telling effect to an audience which was eager to hear such things. In addition, how smartly Vivekananda inserted an autobiographical note, when he mentioned that he would recite a few lines from a hymn that he knew from his earliest boyhood. It revealed his religious preparation and discipline right from his early childhood.

The specifics of his project were presented immediately after drawing an impressive picture of India, its people, and their religion.The present convention, which is one of the most august assemblies ever held, is in itself a vindication, a declaration to the world of the wonderful doctrine preached in Gita. 'Whoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form I reach him, they are all struggling through paths that in the end always lead to Me.'

A Universalist message was presented with a verse from Gita, which certainly supported vividly his earlier thesis about tolerance and universal acceptance apologetics of elitist Hinduism. Vivekananda was never away or distracted from his main purpose.

Then Vivekananda declares:

Sectarianism, bigotry and its horrible descendant, fanaticism, have possessed long this beautiful earth. It has filled the earth with violence, drenched it often and often with human blood, destroyed civilization and sent whole nations to despair. Had it not been for this horrible demon, human society would be far more advanced than it is now.

Vivekananda views humanity as engaged in a process of social evolution. Charles Darwin, the British Naturalist (1809-1882) had just died ten years before the inauguration of the Parliament of World's Religions, leaving behind his widely acclaimed works, experiments, reports and observations proposing a focused theory of evolution. Vivekananda found a powerful ally in the elucidation of his own thoughts and interpretation of the core elements of elitist Hinduism. For an audience that was already well acquainted with Darwin's theory, Vivekananda's speech was most welcome. In addition, the terms such as possessed and demon have their own significance to a Christian audience. Vivekananda achieves a fine blend of Naturalism and Christian metaphor to present his own understanding and interpretation of humanity's ills. And his prescription to cure the humanity of this continuing ill is the acceptance of the basic approach of elitist Hinduism as adumbrated in Gita. Many gurus after him, small and big, would follow this very same path, and achieve great names or disrepute for them in the western nations.

Vivekananda presented rhetoric full of hope:

But its time has come, and I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention will be the death-knell to all fanaticism, to all persecutions with the sword or the pen, and to all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.

Vivekananda's choice of words and phrases and the sequencing of sentences had carried powerful suggestive metaphors. He was not simply presenting some one else's ideas or representing some one else. He was not associating himself with any established organizations or groups. He was representing himself, presenting his way of thinking in a language and idiom that was well understood by his audience. We have no direct evidence to show how his Indian accent helped or hampered the delivery of his speech. He must have delivered his speech in such a manner that most of them understood it, despite his Indian accent. In writing, his speech in response to the welcome accorded to the delegates certainly stands in contrast to the speeches of his compatriots.

AN INDIAN CHRISTIAN'S PLEA - THE SPEECH OF MISS JEANNE SERABJI

The volume reports also the speeches of two other Indian delegates: Miss Jeanne Serabji, a Parsee Christian, and B. B. Nagarkar, a representative of the Brahmo-Samaj.

Miss Jeanne Serabji, a converted Parsee woman, of Bombay, spoke: When I was leaving the shores of Bombay the women of my country wanted to know where I was going, and I told them I was going to America on a visit. They asked me whether I would be at this congress. I thought then I would only come in as one of the audience, but I have the great privilege and honor given to me to stand here and speak to you, and I give you the message as it was given to me. The Christian women of my land said: 'Give the women of America our love and tell them that we love Jesus, and that we shall always pray that our countrywomen may do the same. Tell the women of America that we are fast being educated. We shall one day be able to stand by them and converse with them and be able to delight in all they delight in.'

And so I have a message from each one of my countrywomen, and once more I will just say that I haven't words enough in which to thank you for the welcome you have given all those who have come from the East. When I came here this morning and saw my countrymen my heart was warmed, and I thought I would never feel homesick again, and I feel today as if I were at home. Seeing your kindly faces have turned away the heartache.

We are all under that one banner, love. In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ I thank you. You will hear, possibly, the words in His own voice, saying to you, 'Inasmuch as ye have done it unto the least of these, My brethren, ye have done it unto Me.'

In Miss Serabji's speech, we see anguish for the welfare and equality of Indian women, a project that would not find a focused place or attention in other speeches. This was an earthly speech in a conference of spiritual leaders, and it drew the attention of the audience subtly to the condition of Indian women, and their hopes and aspirations.

The aspiration of Indian women is well portrayed when Serabji quotes Indian women as declaring that 'we are fast being educated. We shall one day be able to stand by them and converse with them and be able to delight in all they delight in.' Unfortunately, this is still a dream for the vast majority of Indian women, and yet there has been tremendous achievement in this area since Indian independence.

Critics have identified that the portrayal of the heroine of the first Tamil novel, Pirataapa Mudaliar Charitram (The Biography of Pratapa Mudaliar) published in 1878, is radically different from the portrayal of women in novels that followed it. Gunasundari, a character developed by Mayuram Munsif Vedanayagam, an eminent Christian writer, is full of confidence and skills, unlike other women characters, which played a diffident and subservient role in such novels. The Indian Christian writer's focus was on the emergence of women as equal partners in the community. Christian programs included the women's emancipation as a necessary element. And we see this reflected in the speech of Serabji. The integration of spirituality and social life is also emphasized in Serabji's speech when she quoted Matthew 25:45 as given above. From her theological perspective, two things are important: to love God and to love your neighbor as yourself. Ministering to and helping humans becomes an integral part of her Christian life. So, her project is the focus on people surrounding her in her land. Note that she easily and deliberately identified herself as an Indian with her Indian brothers.

B. B. NAGARKAR OF BRAHMA SAMAJ

The last from among the Indians who spoke from the platform of the inaugural ceremony was B. B. Nagarkar. The introductory chapter reports that he

"spoke for the Brahmo-Somaj. He said: The Brahmo-Samaj is the result, as you know, of the influence of various religions, and the fundamental principles of the theistic church, in India, are universal love, harmony of faiths, unity of prophets, or rather unity of prophets and harmony of faiths. The reverence that we pay the other prophets and faiths is not mere lip loyalty, but it is the universal for all the prophets and for all the forms and shades of truth by their own inherent merit. We try not only to learn in an intellectual way what those prophets have to teach, but to assimilate and imbibe these truths that are very near our spiritual being. It was the grandest and noblest aspiration of the late Mr. Senn to establish such a religion in the land of India, which has been well known as the birthplace of a number of religious faiths. This is a marked characteristic of the East, especially India, so that India and its outskirts have been glorified by the touch and teachings of the prophets of the world. It is in this way that we live in a spiritual atmosphere."

TO CONCLUDE

Not all Indian faiths were represented. For example, no Sikh representative was mentioned. While there was no Indian Muslim seated on the platform of the inaugural ceremony, the Rev. John Henry Barrows, D.D., chairman of the general committee who welcomed the delegates, said in his welcome speech: "Justice Ameer Ali, of Calcutta, whose absence we lament today, has expressed the opinion that only in this western republic would such a congress as this have been undertaken and achieved." The day certainly belonged to Swami Vivekananda and Indian Vedanta discipline (the cover of the volume displays BRAHMANISM, not HINDUISM). India's spiritual past and its potential for the development of all humanity, rather than the sad plight of the millions in poverty or untouchability, or other social evils that continue to plague the Indian society would be mentioned. The theme was about the past and the emerging awakening of India. Hopes were raised and a demand was made for the recognition of the great contribution of India and for the due place of India among the nations and other religions. Indians of different faiths found a common ground to display their Indian identity and to feel proud about it. A remarkable event in Indian history that took place over 10,000 miles away from the Indian subcontinent, but its pulse would reverberate for more than a century!I intend to present an analysis of the rhetoric of the article by Swami Vivekananda published in the volume in a subsequent issue of LANGUAGE IN INDIA.

CLICK HERE FOR PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION.

SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVES OF CULTURES IN TRANSITION - INDIAN TRIBAL SITUATION | ATTITUDINAL DIFFERENCE AND SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING WITH REFERENCE TO TAMIL AND MALAYALAM | NASTARAN AHSAN'S NOVEL - LIFT - Naming Process and A Call For Socio Political Reform | INDIAN RHETORIC IN THE PARLIAMENT OF RELIGIONS, 1893 - Speeches of Vivekananda and Others | LANGUAGE VITALITY: THE EXPERIENCES OF EDO COMMUNITY IN NIGERIA | RHETORICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ADVERTISING ENGLISH | HOME PAGE | CONTACT EDITOR

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D.

Bethany College of Missions

Bloomington, MN 55438

thirumalai@mn.rr.com

Send your articles

as an attachment

to your e-mail to

thirumalai@bethfel.org.