AN APPEAL FOR SUPPORT

- We seek your support to meet expenses relating to some new and essential software, formatting of articles and books, maintaining and running the journal through hosting, correrspondences, etc. You can use the PAYPAL link given above. Please click on the PAYPAL logo, and it will take you to the PAYPAL website. Please use the e-mail address thirumalai@mn.rr.com to make your contributions using PAYPAL.

Also please use the AMAZON link to buy your books. Even the smallest contribution will go a long way in supporting this journal. Thank you. Thirumalai, Editor.

BOOKS FOR YOU TO READ AND DOWNLOAD

- THE ROLE OF VISION IN LANGUAGE LEARNING

- in Children with Moderate to Severe Disabilities ...

Martha Low, Ph.D. - SANSKRIT TO ENGLISH TRANSLATOR ...

S. Aparna, M.Sc. - A LINGUISTIC STUDY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM AT THE SECONDARY LEVEL IN BANGLADESH - A COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH TO CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT by

Kamrul Hasan, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION VIA EYE AND FACE in Indian Contexts by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - COMMUNICATION

VIA GESTURE: A STUDY OF INDIAN CONTEXTS by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - CIEFL Occasional

Papers in Linguistics,

Vol. 1 - Language, Thought

and Disorder - Some Classic Positions by

M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - English in India:

Loyalty and Attitudes

by Annika Hohenthal - Language In Science

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Vocabulary Education

by B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. - A CONTRASTIVE ANALYSIS OF HINDI

AND MALAYALAM

by V. Geethakumary, Ph.D. - LANGUAGE OF ADVERTISEMENTS

IN TAMIL

by Sandhya Nayak, Ph.D. - An Introduction to TESOL:

Methods of Teaching English

to Speakers of Other Languages

by M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Transformation of

Natural Language

into Indexing Language:

Kannada - A Case Study

by B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. - How to Learn

Another Language?

by M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Verbal Communication

with CP Children

by Shyamala Chengappa, Ph.D.

and M.S.Thirumalai, Ph.D. - Bringing Order

to Linguistic Diversity

- Language Planning in

the British Raj by

Ranjit Singh Rangila,

M. S. Thirumalai,

and B. Mallikarjun

REFERENCE MATERIAL

- UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF LINGUISTIC RIGHTS

- Lord Macaulay and

His Minute on

Indian Education - In Defense of

Indian Vernaculars

Against

Lord Macaulay's Minute

By A Contemporary of

Lord Macaulay - Languages of India,

Census of India 1991 - The Constitution of India:

Provisions Relating to

Languages - The Official

Languages Act, 1963

(As Amended 1967) - Mother Tongues of India,

According to

1961 Census of India

BACK ISSUES

- FROM MARCH 2001

- FROM JANUARY 2002

- INDEX OF ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- JUNE 2005 - INDEX OF AUTHORS

AND THEIR ARTICLES

FROM MARCH, 2001

- JUNE 2005

- E-mail your articles and book-length reports (preferably in Microsoft Word) to thirumalai@mn.rr.com.

- Contributors from South Asia may send their articles to

B. Mallikarjun,

Central Institute of Indian Languages,

Manasagangotri,

Mysore 570006, India or e-mail to mallikarjun@ciil.stpmy.soft.net - Your articles and booklength reports should be written following the MLA, LSA, or IJDL Stylesheet.

- The Editorial Board has the right to accept, reject, or suggest modifications to the articles submitted for publication, and to make suitable stylistic adjustments. High quality, academic integrity, ethics and morals are expected from the authors and discussants.

Copyright © 2004

M. S. Thirumalai

ISSUES IN MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF NORTH-EAST INDIAN LANGUAGES

Vijayanand Kommaluri, R. Subramanian, and Anand Sagar K

This paper was presented in the Workshop on Morphological Analysis conducted recently at the IIT Bombay. LANGUAGE IN INDIA will publish the selected papers of this Workshop in a book form, intially by publishing a few articles in every issue, and then finally putting them all together as a single volume for you to read and download free. The articles represent a bright side of the recent research in Indian linguistics, and thus LANGUAGE IN INDIA http://www.languageinindia.com is proud to publish them for a wider audience. Thanks are due to Veena Dixit and others of IIT Bombay. Thirumalai, Editor.

ABSTRACT

The present paper narrates the minority languages for better understanding and knowledge towards these languages that are present in the North–East (NE) contributing towards the research and development activities in the area of Machine Translation. The NE India, being a linguistic paradise of the country with seven states called Mizoram, Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Tripura, and Manipur has numerous minority languages with rich word power. We had presented several morphological and characteristic features of a majority language amongst the minority languages of NE India with reference towards language engineering. The need of constructing electronic dictionaries, machine translation systems and other accessories for these minority languages is identified. We had emphasised the adverse effects like “language shift and death” towards these languages, unless they are brought to the main stream of the nation in the current era of Information Technology which is transforming the languages into e-Languages. This will contribute in preserving the linguistic heritage of the Nation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Machine Translation (MT) continues to provide a touchstone for Artificial Intelligence (AI) work, and a cause of dispute about the relation of language understanding to knowledge of the world. At the one extreme, there are those who argue that MT cannot be solved until AI has achieved full understanding of natural language by means of programs. India is a country well known for its "unity in diversity". People belonging to different religions, castes, languages, cultures, traditions live together under one roof called "India". The North-East (NE) India is not only rich in natural resources but also in natural languages spoken amongst the people. The NE India consists of seven states popularly known as "seven sisters" namely, Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, Mizoram, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh, and Meghalaya.

In a large multilingual society like India where there is a vast diversity of culture and languages, human communication is a major issue. As the trade and business are widening, people had to migrate for expanding their business activities. In such scenario, every human being is forced to learn more than one language in order to communicate with others. By providing a linguistically cooperative environment which facilitates smooth communication across different linguistic groups, Information Technology (IT) emerges as a catalytic agent in this process. Therefore, there is a need for automated translation systems among various languages in the region.

The immediate solution for such a need is Machine Translation (MT) [Kommaluri, V. 2005]. The major aim of MT is to develop aids for overcoming the language barrier between the technology and the people. Of particular interest is the development of language assessors that allow electronic content on web or other media to be accessible to readers across languages. We had carried out a thorough study on minority languages whose speakers ranging from 10000 to 1000000 exist in India with a special reference to NE India. The NE India is a small geographical region consisting of more than 210 minority languages.

The following section narrates the morphological features of the majority language amongst the minority languages which are present in NE India with State wise break up. In section-3, the issues of language shift and language death are discussed to highlight the hazards of negligence/ignorance towards the minority languages. Our concluding remarks in the section-4 emphasises the need for developing several language accessories, tools and MT systems for these minority languages towards the benefit of the tribal people to access the information in this modernised era of IT.

2. MORPHOLOGICAL FEATURES OF NE INDIAN LANGUAGES

Linguistic diversity is the foundation of the cultural and political edifice of India. The 200 languages enumerated in the Census are a linguistic subtraction of over 1,600 mother tongues reported by the people indicating their perception of their linguistic identity and linguistic difference. The linguistic diversity in India is marked by the fluidity of linguistic boundaries between dialect and language, between languages around State borders and between speech forms differentiated on cultural and political grounds. In spite of diversity, linguistic identity is thin because of the large size of population of the country. Some of the minor languages have more speakers than many European languages. The linguistic differences between the Indian languages, particularly at the grammatical and semantic levels, are less than expected, given their different historical origins. The languages have converged due to intensive and extensive contact making India one Linguistic area. Inter-translatability between those languages is therefore very high.

The languages of India historically belong to four major language families namely, Indo – European, Dravidian, Austro-Asiatic and Sino – Tibetan. The Indo – European has the sub – families, Indo – Aryan and Dardic/Kashmiri, Austro-Asiatic has Munda and Mon-Khmer/Khasi, and Sino-Tibetan has Tibeto-Burman and Thai/Kempti. The Indo-European which is commonly called 'Indo-Aryan’ has the largest number of speakers followed by Dravidian, Austo-Asiatic, also called 'Munda' and Sino-Tibetan which is commonly called the 'Tibeto-Burman'.

NE India consists of the largest number of languages amongst languages that exist in the country. Each state in North-eastern India is multilingual with the minority language speakers varying from 4-30%. Some states like Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh do not have a majority language at all. Such linguistic heterogeneity is found even at the level of district, an administrative unit like the country. The languages of the tribes scheduled by the government are called the 'tribal languages'. Their speakers constitute 4% of the total population, though the tribal population is 7.8%, suggesting language shift among the tribes. Therefore, "perfect" linguistic heterogeneity is found in all the states of NE India.

The ethnic situation in NE India is unique. Unlike the non-tribes who are a part of the Indian caste structure, the tribal societies are, by and large egalitarian, though they do incorporate a degree of ranking. The self-help, self-reliance and community spirit that has sustained them through countries in hostile surroundings is still evident. A spirit of cooperation co-exists alongside competitiveness. The economy has mostly been geared to consumption and substitute, and a market network of some consequence has only lately emerged. Almost around 209 tribes are present in NE India. The following section presents the state wise break up of these languages and morphological features of a majority language amongst the minority languages present in the State.

2.1. ASSAM

Assamese is the principal vernacular and official language of Assam, a NE state of India, and is spoken by 10 million people there and by 10 million more in Bangladesh. An Anglicized derivation of 'Assam', Assamese refers to both the language and the speakers. A descendant of the Magadha Prakrit group of the Indo-Aryan family of languages, it shows affinity with modern Hindi, Bengali, and Oriya. Developed from Brahmi through Devanagari, its script is similar to that of Bengali except the symbols for /r/ and /w/. There is no one-to-one phoneme- grapheme correspondence. Several pidgins from various linguistic families namely English, Arabic, Austric, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Parsi etc., have enriched the Assamese vocabulary. Most of the tribes in Assam belongs to Tibeto-Burman family and speaks their own respective languages of that family. The Ahoms who came to Assam in the early part of the thirteenth century, were speakers of the 'Thai' language, a branch of Siamese-Chinese linguistic family. Slowly they shifted their language to Assamese.

The characteristic phonemic features of Assamese include a voiceless velar fricative /x/, the alveolar fricatives /s/ and /z/, alveolar plosives, the alveolar nasal /ņ/, only one /r/, and the intervocalic occurrence of /ŋ/. Characteristic morphological features are as follows:

- Gender and number are not grammatically marked.

- There is lexical distinction of gender in the third person pronoun.

- Transitive verbs are distinguished from intransitive.

- The agentive case is overtly marked as distinct from the accusative.

- Kinship nouns are inflected for personal pronominal possession.

e.g., dueta 'father', dueta-r 'your father', dueta-k 'his father';

- Adverbs can be derived from the verb roots.

e.g., mon pokhila uradi ure 'The mind of flies as a butterfly flies'.

- A passive construction may be employed idiomatically.

e.g., eko nuxuni 'Nothing is audible'.

Syntactically it is non – distinct from its genetic relatives. Assamese has no caste dialects but a geographical dialect kamrupi with further sub-dialects. Written Assamese is almost identical with colloquial. An Assamese-based pidgin or Nagamese is spoken in Nagaland. Mutual convergence with neighbouring Tibeto-Burman languages and Bengali is spoken in Assam is noticeable in phonology and vocabulary. Its indigenous vocabulary is gradually falling into disuse in favour of Sanskritized forms.

2.2. TRIPURA

Most of the scholars believe that the Tripura royal family originally belonged to the Tipera tribe. The Tipera tribe, like the Cachari and other tribes of eastern India, is Mongolian in origin. The Tipera or Tripuri tribe is classified under the Indo-Mongoloids or Kiratas. Linguistically, the Tiperas’ are Bodos’. The language of the Tripuris' is known as Kakbarak. It belongs to the Tibeto-Burman group of languages, and its roots can be traced to the Sino-Tibetan family of speeches. It strongly resembles other dialects, such as Cachari and Garo. We have seen that for historical reasons, Bengali has been the most important and dominating language in the state. Almost the whole population of Tripura is Bengali-speaking, and there are sizable Bengali communities in almost all states of the NE India.

Bengali is probably the most widespread language in the entire NE India where Bengali speaking communities have migrated to all the places in NE for various reasons. Bengali is an Indo-Aryan language and forms, with its close relatives Assamese and Oriya, the most easterly development of the Magadhi branch of Middle Indo-Aryan. Bengali is the national language of Bangladesh with about 150 million speakers and the state language of West Bengal in India with about 86 million speakers. One third of the population of Assam speak Bengali, and Barak Valley which comprises of three districts of Assam namely Cachar, Hailakandi, Karimgang, majority people who have migrated from Sylhet in NE Bangladesh speak Sylheti, the dialect of Bengali. Bengali script is a cursive script with 12 vowels and 52 consonants and reads from left to right. It is organized according to syllabic rather than segmental units. There is a horizontal line above the characters. There is no distinction between upper and lower cases.

Bengali uses a script that was originally used for the writing of Sanskrit in NE India. Virtually all the Sanskrit consonantal distinctions like aspirated/inspirited, dental/retroflex, etc., have survived in Bengali and as in Sanskrit, consonants are considered to carry an 'inherent' vowel sound unless another vowel is added. Bengali verbs follow a very regular pattern, falling into five main classes according to stem vowel, which ‘mutates’ between э/o, ć/e, e/I, o/u or a/e. Thus amI sunI means I hear but se śone means he/she hears. Similarly tumi răkhbe means you will put but ămră rekhechi means we have put. Verb stems can often be ‘extended’ to give a causative meaning. Thus ămi dekhi is translated as I see but ămi dćkhăi derives I show. There is a unified article/demonstrative/pronoun system, with no distinction of gender. Thus e means ‘he/she nearby’, eţă means ‘this’, e băŕiţă means ‘this house’, and băŕiţă means ‘the house’, o means ‘he/she over there’, ogulo means ‘those’, o chabigulo means ‘those pictures’.

Cardinal numerals take the definitive article suffix, but not for measurements. For example păcţă ceyăr gives the meaning of ‘five chairs’ but păc măil means ‘five miles’. The diminutive article –ţi is used for people, and for small or attractive things for example cheleti means ‘the boy’, duţi phul means two flowers. The meaning of ćkţă/ekţi is ‘one’ and can function as an indefinite article, but is often omitted. There is no indefinite plural suffix: kalam can mean ‘(a) pen’ or ‘pens’. There are four cases, which can be added to the noun or to the definite article as follows:

- Ř for the nominative,

- -ke for the accusative/dative,

- -r/-er for the genitive,

- -e/-te for the instrumental/locative.

In the plural there are case endings for personal nouns. For non-personal nouns the singular endings are added to the plural definite article. Personal pronouns make use of the same endings. There are post positions rather than prepositions. Participles are preferred to subordinate clauses and are frequently used to make idiomatic compound verbs. For example: neoyă (take) combined with ăsă (come) make niye ăsă (fetch/bring). The impersonal constructions are used for possession and obligation and for events and circumstances that are passive rather than active. For example:

ămăr gări ache means ‘I have a car’ (lit. ‘of me car is present’)

oke śikhte habe means ‘he/she will have to learn’ (lit. ‘him/her to learn will be’)

băbăr asukh hayeche means ‘Father is ill’ (lit. ‘of Father illness has become’).

The basic word order is Subject – Object – Verb. For example, in English one would say, “I speak Bengali” and in Bengali, “I Bengali speak.” A preposition would fit into the structure thus: SOPV. For example, “I shop to go”. Bengali has been characterized as a rigidly verb-final language wherein nominal modifiers precede their heads; verbal modifiers follow verbal bases; the verbal complex is placed sentence-finally; and the subject noun phrase occupies the initial position in a sentence.

2.3. MEGHALAYA

Khasi and Garo are the dominant languages of the State of Meghalaya, a hill state comprising the former Khasi and Jaintia Hills and Garo Hills, District of Assam. The Garos’ living in greater Mymensingh and in the hilly Garo region of Meghalaya in India, speak hilly Garo or Achik Kata.Garo belongs to the Mon-Khmer language family which is a subgroup of Austro-Asiatic.The Khasi phonological system is characterized by its opposition of plain versus aspirated versus voiced sounds, a limited possibility of consonant clustering of maximal two phonemes syllable-initially, the limitation of phonemes at the end of a syllable consisting of unreleased sounds /k/, /_/ (id/it) /t/ and some other phonemes as can be seen below in the chart, a contrast of short and long vowels and no tones. Free morphemes are mostly one-syllabic or disyllabic with the first syllable consisting of vocalic nasals or sonant (/_m/(ym), /_n/ (yn), /_ń/ (yn), /__/ (yng), /_r/ (yr), /_l/ (yl) .The phonemic chart of “ka tien Sohra” (language of Cherrapunji) is as follows.

Consonants:

Voiceless un-aspirated: p t k _ (y/h)

Voiceless aspirated: ph th kh

Voiced: b d d_ (j)

Spirant voiceless: {f} (ph /f) s _ (sh) [English: ship] h

Sonants trill & lateral: r l

Nasals: m n ń (ń /in) _ (ng)

Semi-vowels: w j (i / ď /) [as y in English year]

Vowels: a <> a: (a)

_ (e) <> e: (ie) _ (o) <> o: (u)

u (u) i (i)

Consonants syllable final:

p t _ (id/it) k _ (h)

m n ń (-in/ ń ) _ (ng)

w j (i)

If the written form of a phoneme is different it is added in parantheses ( ).

If the written form of a phoneme is different it is added in paranetheses ( ). Morphology is characterized by the exclusive use of prefixes and free morphs for grammatical processes. Infixes as in other Mon-Khmer languages are not used anymore and remain only as lexemes, for e.g. shong (to live, to sit) and shnong (village). A peculiar feature that is shared with other non-related languages of the area, as Mikir or Garo, is the loss of an obviously former prefix in the formation of compounds, as ‘u sew beh mrad” ‘a hound’ from ‘u’ (article) + ‘ksew’ ‘dog’ + ‘beh’ ‘to chase’ + ‘mrad” ‘animal’ or ‘rangbah’ ‘an adult male’ from “shynrang” “man, male” + “bah” “be grown, be big”. Khasi itself is divided into numerous dialects, as there are Pnar or Synteng, Lyngngam, Amwi, Bhoi etc. Khasi is a recognised language of the 6th schedule.

Rev. Jones started experimenting with the Welsh alphabet using the Welsh letter c (always pronounced as [k]) for the Khasi phonemes /k/ and /kh/, so that the Khasi words “ka kitap” (the book) appeared as ca citap. It was found that the letter c was not suitable and he used k instead but left this k at the place of c so that the Khasi alphabetical order is “a, b, k, d…” The introduction of the letter k allowed him to differentiate the relevant phonemes /k/ and /kh/. Another unique feature of the Khasi alphabet was the introduction of the digraph /ng/ [_] as a separate letter in the alphabet following the letter “g” which was not used at all separately. To introduce a writing system for an unwritten language is always an uncertain matter regarding its acceptance by the people aimed at but regarding Khasi it worked out well. Another problem was the selection of the right “dialect”. Rev. Jones chose the language of Sohra (Cherrapunji) which proved to be a good choice later on. The spelling system was not perfect and soon dissenting voices appeared among the Khasis’ who became literate very quickly. Later on two more letters were introduced, ń and ď, the first one for the palatal nasal [_] and the second one for the phoneme /j/ [j] (as in year). The letter y could not be used because it had two different functions: to represent the schwa [_] in the syllabic letters written yn [_n], ym [_m], yng [__], yr [_r], yl [_l] where the y is pronounced like the ‘a’[_] as in English “above,” and to represent the glottal stop following a consonant and preceding a vowel as in syang [s_a_] “to roast, to toast”.

Another problem not yet solved satisfactorily till today is the representation of short and long vowels. There is a tendency to write the sign of the voiced consonants after a long vowel, e.g. “ka ngab” [ka __a:p] “the cheek” and “kangap” [ka __ap] “the bee” but in words ending in no sound a differentiation is not possible. In course of time, however, a certain tradition in writing particular words has been established. After the introduction of the Latin alphabet and its acceptance by the people the knowledge of written Khasi in Roman characters grew steadily.

2.4. MIZORAM

Mizoram known as the Lushai Hills District till 1954 is now a state in the Indian Union. The word ‘Mizo’ is a generic term applying to all Mizos living in Mizoram and its adjoining areas of Manipur, Tripura and the Chittagong Hill tracts and Chin Hills. Mizo literally means (Mi = people, zo = highlander) ‘Highlander’.

The language of the Mizo comes under the Tibeto–Burman branch of Sino–Tibetan group of people like Naga, Mirki, Miri, etc. The numerous clans of the Mizo had respective dialects, amongst which the Mizo dialect, originally known as Duhlian, was most popular which subsequently had become the lingua franca of the State. Initially the Mizo had no script of its own. Christian missionaries started developing script for the language adopting Roman script with a phonetic form of spelling based on the well known Hunterian system transliteration. Later there were radical developments in the language where the symbol â used for the sound of long O was replaced by aŵ with a circumflex accent and the symbol A is used for the vowel sound of O was changed to AW without any accent. The following few words shall suggest that Mizo and the Burmese are of the same family.

To illustrate the words that are same as Burmese are: Kun (to blend), Kam (bank of a river), Kha (bitter), Sam (hair), Mei (fire), That (to kill), Ni (Sun) etc. In Mizo the large groups of words are obviously related to one another both in sound and in meaning, but not by any regular systematic pattern. For example: bu (slightly bulging), bum (to swell up, be swollen), bom (to bloat), bem (chubby), hpum (fat), bum (hill, mountain, heap), pem (to bank up earth into a hillock for planting), hpum (to crouch), bong (to bulge, to grow, as a goitre), bep (calf of the leg – the bulging part), um (round/bulbous). These are all obviously relatable semantically to a notion of bulging or protrusion, and they share a back vowel and a labial initial or final consonant or both. However, the relationships are not regular, i.e., there is no general pattern in which, for example, an adjective is related to a verb by suffixation of a nasal, as bu is to bum in the preceding series.

Mizo is a tone language, in which differences in pitch and pitch contour can change the meanings of words. Tone systems have developed independently in many of the daughter languages largely through simplifications in the set of possible syllable-final and syllable-initial consonants. Typically, a distinction between voiceless and voiced initial consonants is replaced by a distinction between high and low tone, while falling and rising tones develop from syllable-final (h) and glottal stop, which themselves often reflect earlier consonants.

Mizo contains many un-analyzable polysyllables, which are polysyllabic units such as the English word water, in which the individual syllables have no meaning by themselves. In a true monosyllabic language polysyllables are mostly confined to compound words, such as lighthouse. Most Tibeto-Burman languages do show a tendency toward mono-syllabicity. The first syllables of compounds tend over time to be distressed, and may eventually reduce to prefixed consonants. Virtually all polysyllabic morphemes in Mizo can be shown to originate in this way. For example, the disyllabic form bakhwan "butterfly," which occurs in one dialect of the Trung (or Dulung) language of Yunnan, is clearly a reduced form of the compound blak kwar, found in a closely related dialect. The first element of this compound, in turn, is itself a reduction of an old compound of two roots, ba or ban and lak, both meaning ‘arm’, ’limb’, and often turning up in forms for ‘wing’.

2.5. MANIPUR

Described by Lord Irwin as the 'Switzerland of India,' Manipur boasts of an exotic landscape with gently undulating hills, emerald green valleys, blue lakes and dense forests. Manipuri is spoken by about 2 to 2.5 million people in Bangladesh, Tripura, Assam and Myanmar. Nearly half a million Manipuri speaking people live in greater Sylhet. Manipuri language is about 3,500 years old and belongs to the Kuki-Chin group of the Tibeto-Burmese stream of the Mongoloid family of languages. Up to the middle of the 19th century this language was known as Moitoi after the name of a tribe. In the original Moitoi there were 18 letters. Other letters were added later. The letters are pronounced similar to the sounds commonly found in the Tibetan family. The Manipuri language began to be written in the Bangla script when VAISNAVISM assumed the form of the state religion during the days of Maharaja Garib Newaz in the 18th century. The verbal forms change following number, gender or the subject as shown below:

Table – I: Examples

|

Person |

Singular |

Plural |

|

Ist |

Mi Jauriga (I am going). |

Ami Jiarga (We are going). |

|

IInd |

Ti Jarga (You go). |

Tumi Jaraiga (You go). |

|

IIIrd |

Ta Jarga (He goes), Ta Jakga (He may go). |

Tanu Jitaraga (They go), Tanu Jakaga (They may go). |

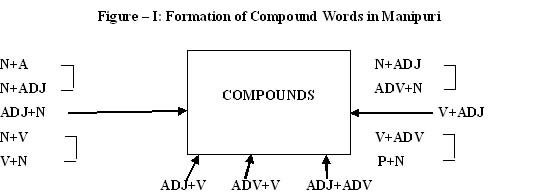

Word making has taken place as a result of a number of linguistic processes, such as word composition, derivation, back formation, hybridism, word clipping, shortening and root creation, imaginative and grammatical affinity. Word composition can be explained as compound method. Joining two or more base or root words forms a compound word or simply a compound. The new word, thus formed, is used to express a meaning that could be rendered by the phrase of which the simple words form parts. Of course, the new word, formed, may or may not have any link or relation with the sense of each base word. In the Manipuri language, compound words are formed freely, and this has enriched, to a very extent, the native vocabulary. By joining two or more part of speech may make the compounds. There may be the compounds of two or more nouns, noun and pronouns, nouns and verbs, nouns and adjectives, nouns and adverbs, adjectives and verbs, adverbs and verbs, adjectives and adverbs etc. as shown in the following picture. Thus, the Manipuri compounds are found formed in different ways that is narrated through the following diagram.

Derivation can also be explained as derivatives in Manipuri. The true life-blood of a language lies in its words by derivation. However, numerous foreign loan words may be, it is the process of forming new words from native resources that constitutes the genius of a language. The formation of words by means of derivation has taken place in the Manipuri language in a number of ways, and all these indicate the great potency as well as flexibility of the Manipuri language. A large number of new words in Manipuri can be built from parts of speech, from prefixes and suffixes, from word composition, from back-formation and from shortening by means of derivation. Derivation means the making of a new word out of an old one. It is one of the richest sources of forming a large number of new words in Manipuri.

Hybridism is the process of forming new composite words from the stems of different languages. When a prefix or suffix is added from one language to an original word of another language, the new word, thus, formed, is called a hybrid. The principle of hybridism is found operative in the formation of new word by the combination of Manipuri and Bengali, Manipuri and English, and so on. Word clipping is one of the sources of forming new words. There is a general tendency to mono-syllabi’s. This has led to the numerous popular clippings of long foreign words. These clippings have been done in Manipuri in different ways.

Root creation is one of the processes of forming new words. The principle of root creation, of course, is not easily definable or founded on any exactly logical method. In fact, the term is applied somewhat vaguely, to the process of the formation of those words, which awe their origin neither to native resources nor to foreign influence. There are really a good number of words in Manipuri, which do not belong to old Manipuri or to any foreign language. These are not also formed out of the linguistic process of word composition and derivation. The method of the formation of such words is characterized as root creation. Word making by means of root creation in Manipuri has several forms. The imaginative method has been adopted in case of words in course of time have developed semantic connotations very widely removed from there etymological meanings. In such cases, the makers of Manipuri have restarted to a purely imaginative and creative process by which the new word evolved by them expresses the present connotation of the original word without reference to its structural form or literal meanings. According to the method of grammatical affinity, new words have been coined in Manipuri on the basis of root meanings of the original terms giving to these words a recognizable grammatical affinity with their present words. One of the resourceful means in word formation is the process of back formation. This is the process to form new words by subtracting something from some old existing words. In other words, the words in some cases are formed from the back, and so the process is called “Back formation”. Precisely, word making in Manipuri is in front side like Hindi, Bengali and other Indian leading languages. It is standing in front side.

The Meitei language had its own script which has an apparent semblance to that of the Tibetan. The Manipuri character is like that of Bengali in Brahmi style, written from left to right. The second has no merit of consideration at all as the Manipuri and Chinese systems of writing are distinctly different. We may, for a while, examine the origin of scripts of languages close to Manipuri. The Meitei script evolved out of Brahmi is quite evident and there are four sub-branches of Brahmi, two of which spread to NE and North India. Similar to the vowels of present day Hindi of Wardha, Meitei vowels are formed with the addition of signs to the root vowel ‘a’.

2.6. NAGALAND

For a small state like Nagaland having a small population, a considerable linguistic heterogeneity is noted. There are as many as twenty languages, such as Angami, Ao, Bodo/Boro, Garo, Kacha Naga, Khezha, Khiemnungan, Konyak, Lotha (Kyon), Mao, Phom, Rengma, Sangtam, Sema, Tangkhul, and Zemi Naga. All Naga languages belong to the Tibeto-Burman family of languages. All Naga languages adopt the Roman script, as they do not have script of their own. Other languages spoken in the State are Hindi, Bengali, Assamese, Malayalam, Oriya, Punjabi, Nepali/Gorkhali, Manipuri/Meitei and Urdu.

A very interesting finding is that while the non-tribes are bilingual in only other languages of the Indo-Aryan family or English, the tribal people are bilingual in English, Assamese, Hindi and adjacent tribal languages, in that order. Among the Nagas divided by their languages, Nagamese may be treated as the lingua franca of the state, and has been claimed by thirteen communities as a language spoken at bilingual level.

There are 7 vowels and 21 consonants in Tangkhul – Naga. As supra segmental features, there are tones, length and nasality. The vowels are nasalized in the vicinity of nasals consonants. Inter-nasal vowels are vowels which are always nasalized while pre-nasals or post-nasals are slightly nasalized. Nasalization of vowels, therefore, is not phonemic and the nasal vowels are the contextually conditioned variants of the oral ones. Also, there is a large number of freely varying varieties of vowels and vowel clusters conditioned by different pitch heights and intonations. Detailed description of the consonants, supra-segmental is shown the following tables.

Table – II: Consonants

|

|

|

Bila-bial |

Labio-dental |

Dental alveolar |

Palatal |

Velar |

Glottal |

|

O b s t r u e n t s |

Plosive |

p ph |

|

t th |

c |

k kh |

? |

|

Fricative |

|

F |

z s |

|

|

h |

|

|

Nasal |

m |

|

n |

|

η |

|

|

|

S o n o r a n t s |

Lateral |

|

|

l |

|

|

|

|

Thrill |

|

|

r |

|

|

|

|

|

Approximant |

w |

v |

|

Y |

|

|

Table – III: Supra segmental:

|

1 |

Length |

= |

: |

|

|

2 |

Nasality |

= |

~ |

|

|

3 |

Tones |

High |

= |

(e.g. phá = rt. of ‘good’) |

|

|

|

Mid |

= |

Not marked (e.g. pha = rt. of ‘search’) |

|

|

|

Low |

= |

(e.g. phŕ = rt. of ‘pluck’) |

There are 11 vowel sounds in Tangkhul – Naga. All the vowels except [u], [o] and [∂] have allophones. [i], [e], [a] and [ü, ū] respectively. The difference between tense and lax pairs such as [i] and [I], [e] and [ε], [a]and [ā] is not very significant in the sense that they are in free variation and their differences are not predictable in terms of their position in a word. Comparatively, the difference between the allophones [ū] and [ü] is easily predictable with respect to their position in a word. For the remaining vowel phonemes and allophones the following examples show only the ‘more acceptable’ pronunciation. There are seven types of diphthong in Tangkhul – Naga. They usually occur in syllable final position. Initial vowel sequence is found only in expressive word and some affixes as shown below.

Table – IV: Examples for affixes in Thangkul – Naga

|

Medially |

Finally |

|||

|

ei |

sčěhá |

Prayer |

mei |

fire |

|

|

keinú η |

City |

kh∂leì |

squirrel |

|

eo |

réósa |

name of a children’s game |

k∂méó |

God, demon |

|

|

|

|

teo |

small |

|

∂u |

th ∂una |

Courage |

th ∂u |

concern |

|

|

c∂uki |

Chair |

c∂ú: |

yelling sound in hunting |

|

ai |

láírik |

Book |

kháí |

fish |

|

|

ráíci |

Scabies |

mai |

face |

|

ao |

karkŕň |

Spider |

yŕň |

sheep |

|

|

nŕňmei |

Gun |

páó |

news |

|

oi |

---- |

|

šoi |

signature |

|

|

---- |

|

šňě |

to fail |

|

ui |

můěya |

Cloud |

kh ∂̀ můě |

bread |

|

|

kúírü |

mister, sir |

kúí |

|

2.7. ARUNACHAL PRADESH

Arunachal Pradesh is marked by an extraordinary range of heterogeneity in terms of cultural and linguistic traits within and between the tribal groups. Although it is a small state, as many as 42 languages are spoken in it. All the languages except the two Indo-Aryan languages, Assamese and Nepali, belong to the Tibeto-Chinese language family.

Among the Tibeto-Chinese languages, Khampti-Shan belongs to the Siamese-Chinese sub-family, while the others belong to the Tibeto- Burman sub-family. Of the 42 languages, 40 are tribal languages. Assamese and Nepali are the scheduled languages. The 15 sub-groups of the Thangsa tribe, the Monpa language by the six sub- groups of the same tribe, and the Mishmi language by the three sub-groups of the same tribe speak Tibetan. The respective tribal groups speak the rest of the languages. The Khamiyangs claim Assamese as their mother tongue. The tribal languages are: Adi, Bodo/Boro, Mikir, Mishmi, Monpa, Nishi/Daa, Nocte, Tangsa and Wancho. Nefamese (Arunachalese), a variant of Assamese whose morphological features are presented in Section 2.1, is the lingua franca among tribes, and between tribes and non-tribes. As many as six different scripts are in use. They are Assamese, Devanagari, Hingma, Mon, Roman, and Tibetan.

3. LANGUAGE SHIFT AND DEATH

When members of an ethno-linguistic group, starts using the language of another for domains and functions hitherto preserving their own language, the process of language shift is underway. In extreme cases a group's language may cease to be spoken at all. A number of factors account for language shift, the most important being changes in the way of life of a group which weaken the strength of its social networks (urbanization, education), changes in the power relations between the groups, negative attitudes towards the stigmatized minority language and culture, or a combination of all three. Language shift has been studied from various perspectives: sociological and demographic at the macro level, ethnographic, social psychological, and so on, at the micro level, each approach making use of specific research methods and techniques which are not contradictory but complementary.

A language dies when it no longer has any speakers. 'Language death', deals with linguistic extinction. It is the extreme case of language contact where an entire language is borrowed at the expense of another. It involves language shift and replacement where the obsolescent language becomes restricted to fewer and fewer individuals who use it in ever fewer contexts, until it ultimately vanishes altogether. Researchers seek general attributes of dying languages, but realize that the circumstances that lead to language death may vary considerably from community to community and from speaker to speaker. There are different types of language death with associated characteristics follow [Campbell and Muntzel, 1989]. These situations are not mutual exclusive and may overlap.

- Sudden Language death involves the abrupt disappearance of a language because almost all of its speakers suddenly die or are killed.

- Radical language death is like 'sudden death'. Language loss is rapid usually due either to severe political repression and genocide, where speakers out of self defence stop speaking the language, or to rapid population collapse due to destruction of culture, epidemics, etc (Dressler, 1981; Hill 1983). Radical language death can leave rusty speakers, and semi-speakers. Thus, radical language death can lack the age-gradation 'proficiency continuum' more typical of gradual language death.

- Bottom-to-top language death is where the repertoire of [stylistic] registers suffer attrition from the bottom up (Hill, 1983), remaining only in formal or ritual genres. This has been called the 'Latinate pattern', here the language is lost first in contexts of domestic intimacy and lingers on only in elevated ritual contexts (Hill 1983; Moore 1988).

- Gradual language death is the most common loss of language contact situations. Such situations have an intermediate stage of bilingualism in which the dominant language comes to be employed by an ever-increasing number of individuals in a growing number of contexts where the subordinate language was formerly used. This typically exhibits a proficiency continuum determined principally by age. Younger speakers have a greater proficiency in the dominant language and learn the obsolescing language imperfectly; they are called 'semi- speakers'.

These situations are not mutual exclusive and may overlap. Language shift and language death adversely affect the state of societal bilingualism in the world and should be better understood if languages and cultures are to be preserved.

4. CONCLUSION

In the present paper, we had identified the minority languages and elaborated thoroughly the morphological features of a majority language amongst the minority languages for each State that are present in the multi-lingual society called NE India. This is a fascinating field which, we do believe, will be explored in still greater depth in the future.

India being a multilingual country had already recognized the potential of multilingual computing and some of the programs to build competency were initiated more than a decade ago. Since then slowly and steadily many research, development and application oriented activities have been built up at the government, public and private organizations [Kommaluri V., 2003]. This has resulted in creating an awareness about the use of computers in the areas of language analysis, understanding and processing. Preparatory works for building corpora of contemporary texts have led to the development of potential applications like e-dictionaries, morphological analyzers, spell checkers, etc. Defining and refining standards, development of operating systems, human machine interfaces, Internet tools and technologies, machine-aided translations and speech related efforts are some of the major thrust areas identified for attention in the near future. Besides constructing language engineering accessories, automatic machine translation systems are essential for improving the knowledge base of the minority languages by translating the enormous literature being published everyday in the world. This shall be made possible by adopting the example based machine translation methodology (Kommaluri, V. et al., 2002) as majority of the minority languages belongs to Tibeto-Burman family of languages.

Unless these minority languages are brought into the mainstream, there is every chance of these languages lose their existence and die during the present transformation of communication networks through languages to electronic form of communicating languages called “e-Languages”.

References

· ALPAC: 1966, Languages and Machines: Computers in Translation and Linguistics, National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council Publication 1416, Washington, DC.

· Bhat, D. N. S. (1997). Manipuri Grammar, Volume 04 of LINCOM Studies on Asian Linguistics. Lincom GmbH, München.

·

Bharati, Akshar, Vineet Chaitanya and Rajeev

Sangal: 1995, Natural Language Processing: A P![]() ninian Perspective, New Delhi, Prentice Hall of India.

ninian Perspective, New Delhi, Prentice Hall of India.

· Bloomfeild L: 1933, Language, Henry holt, New York.

· Boruah, B. K. (1993). Nagamese: the Language of Nagaland. Mittal Publications, New Delhi.

· Campbell L, Muntzel M: 1989, The structural consequences of Language death. Investigating Obsolescence: Studies in Language Construction and Death, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

· Campbell, George L, Compendium of the World’s Languages, vol. 1, Routledge, London/New York.

· Census of India: 1991 series, Office of the Registrar General, New Delhi.

· Comrie, Bernard, ed: 1987, The World’s Major Languages, Oxford University, NY.

· Dave S., Parikh J. and Bhattacharyya P: 2002, Interlingua Based English Hindi Machine Translation and Language Divergence, Journal of Machine Translation (JMT), Volume 17.

· Dressler W U:1981, Language Shift and Language Death – A protean challenge for the linguistic, Linguistica 15: 5-27.

· Gaarder B: 1977, Language Maintenance or language shift, In: Mackey W F, Andersson T (eds.), Bilingualism in Early Childhood, Newbury, Rowley, MA, 1977.

· Giridhar, P. P. (1994). Mao Naga Grammar. Central Institute of Indian Languages: Grammar Series. Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore.

· Grierson, G. A. (Ed.) (1903a). Indo-Aryan Family: Eastern Group: Specimens of the Bengali and Assamese Languages, Volume V part I of Linguistic Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Goverment Printing, Calcutta.

· Grierson, G. A. (Ed.) (1903b). Tibeto-Burman Family: Specimens of the Bodo, Naga, and Kachin Groups, Volume III Part II of Linguistic Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Goverment Printing, Calcutta.

· Grierson, G. A. (Ed.) (1904a). Mon-Khmer and Siamese-Chinese Families (Including Khassi and Tai), Volume II of Linguistic Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Goverment Printing, Calcutta.

· Grierson, G. A. (Ed.) (1904b). Tibeto-Burman Family: Specimens of the Kuki-Chin and Burma Groups, Volume III Part III of Linguistic Survey of India. Office of the Superintendent of Goverment Printing, Calcutta.

· Grierson, G. A: 1995, Languages of North-Eastern India, Gian Publishing House, New Delhi.

· Haldar G: 1986, A Comparative Grammar of East Bengali dialects, Puthipatra, Calcutta.

· Hill J: 1983, Language Death in Uto-Aztecan, International Journal of American Linguistics, 49: 258-276.

· K. S. Singh.: 1992, People of India-An Introduction, Seagull Books, Calcutta.

· K. S. Singh: 1994, People of India-Nagaland, Volume XXXIV, Anthropological Survey of India, Calcutta.

· K. S. Singh: 1995, People of India-Arunachal Pradesh, Volume XIV, Anthropological Survey of India, Calcutta.

· K. S. Singh: 1995, People of India-Mizoram, Volume XXXIII, Anthropological Survey of India, Calcutta.

· Kommaluri Vijayanand, S I Choudhury and Pranab Ratna: 2002, VAASAANUBAADA: Automatic Machine translation of Bilingual Bengali-Assamese News Texts, Language Engineering Conference (LEC 2002), Hyderabad, India, IEEE CS Press, CA, pp. 183 - 188.

· Kommaluri Vijayanand, Subramanian R and Anand Sagar K: 2005, Information Technology: Trends towards Research in North – East India, Proc. of Sixth Int’l Conf on South Asian Languages (ICOSAL – 6), Hyderabad, India.

· Kommaluri Vijayanand and Anand Sagar K: 2003, Information and Communication Technology: An Indian Perspective, Proc. of First Seminar on i4d, Map Asia 2003, KL. Site last visited: March 22, 2005. www.i4donline.net/seminar/i4dp005.htm

· Moore R: 1988, Lexicalization versus lexical loss in Wasco-Wishram Language Obsolescene, International Language of American Linguistics, 54: 453-68.

· Pryse, W: 1855, An introduction to the Khasi language: Comprising a grammar, selections for reading, and a vocabulary. - Calcutta: School-Book Soc., - X, 192 S.

· Schermerhorn R A: 1970, Comparative Ethnic Relation: A frame Work for Theory and Research, Random House, New York.

· Sirajul Islam Choudhury, Leihaorambam S. Singh, Samir B, Pradip Kr. Das: 2004, Morphological Analyzer for Manipuri: Design and Implementation, AACC 2004: 123-129

· Sten, Harriswell Warmphaign: 1993, Ka grammar/da u H. W. Sten. - Rev. ed. Shillong: Khasi Book Stall, 1993. - VIII, 128 S.; (Khasi) [Khasi-grammar].

CLICK HERE FOR PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION.

LANGUAGE ATTITUDE OF THE ORIYA MIGRANT POPULATION IN KOLKATA | CORPUS BASED MACHINE TRANSLATION ACROSS INDIAN LANGUAGES - FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE | ISSUES IN MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF NORTH-EAST INDIAN LANGUAGES | GREETINGS IN KANNADA | LANGUAGE POLICY OF THE INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS DURING THE PRE-PARTITION PERIOD 1939-1946 | HOME PAGE | CONTACT EDITOR

Vijayanand Kommaluri

Department of Computer Science

Pondicherry University,

Pondicherry – 605 014, India

kvixs@yahoo.co.in R. Subramanian

Department of Computer Science

Pondicherry University,

Pondicherry – 605 014, India

subbur@yahoo.com Anand Sagar K

PSI Data Systems

Bangalore

India

anand.sagar@psidata.com

Send your articles

as an attachment

to your e-mail to

thirumalai@mn.rr.com.